Reef keeping aquarists develop an aesthetic judgment about what’s “cool” to keep in their aquariums, and they are often influenced by the rarity of a particular type of creature. While I too admire a rare specimen, I have always been and will always be impressed by such common things as “button polyps,” the many-hued and mostly simple to care for zoanthids.

Zoanthids form clusters of polyps and encrusting mats commonly referred to as “sea mat,” “false coral,” or “colonial anemones,” and they are sometimes erroneously called “soft corals.” The polyps can be solitary, connected by a creeping tissue called coenenchyme that may form stolons or lamellae, or they may be embedded in a thick massive coenenchyme. They are normally attached to any hard substrate, though some genera are associated with specific “host” organisms and grow only on them.

Zoanthids are relatives of corals and anemones, and are included with them in the phylum Cnidaria (formerly Coelenterata), in the class Anthozoa, but the zoanthids comprise the distinct order Zoanthiniaria (formerly Zoanthidea) in the subclass Zoantharia that also includes sea anemones, corallimorphs, and scleractinian corals. Zoanthids differ from true sea anemones, which belong to the subclass Actiniaria, based on details of their internal anatomy and the fact that zoanthids form true colonies in which the individual polyps are connected by a common tissue, the coenenchyme. True anemones may divide to form beds of adjacent clones, but they are not connected. Zoanthids lack a fossil record, but they are considered more closely related to the extinct “corals” known as Tabulata and Rugosa than to other anthozoans.

The order Zoanthiniaria is subdivided into the suborder Brachycnemina, which includes the families Zoanthidae and Neozoanthidae, and the suborder Macrocnemina, which includes the family Epizoanthidae and Parazoanthidae. The structural difference between these groups is shown in Delbeek and Sprung (1997).

Genera

Zoanthids commonly kept in aquaria belong mainly to six genera, Zoanthus, Protopalythoa, Palythoa, Isaurus, Acrozoanthus and a possible new genus for the zoanthid commonly called “yellow polyps.” There are other genera that are occasionally harvested for aquaria, including Neozoanthus, Parazoanthus, and Epizoanthus. I believe there are also some additional undescribed genera that occasionally are harvested from Indonesia. One is an extremely small-polyped Zoanthus-like variety; the other is a relative of yellow polyps and Acrozoanthus, with an appearance and colony form somewhere between the two. A third is quite like this latter one but forms dense colonies like Zoanthus, but with distinctly elongate tentacles. I show this one, which I call Zoanthus sp? in this article. The solitary polyp zoanthid, Sphenopus, a solitary polyp species, is not harvested for aquaria, nor is Gerardia, the only zoanthid known to form a skeleton. The genera Thoracactis and Isozoanthus in the family Parazoanthidae are also poorly known, and not likely to be seen in an aquarium.

The author found this unidentified, large, non-photosynthetic zoanthid in the Solomon Islands during a night dive. It was under a ledge and the tentacles were expanded.

Typical daytime appearance of “Snake Polyps,” Isaurus tuberculata. Sometimes the columns are fluorescent green or have iridescent metallic spots.

This recently imported Zoanthus sp. is unusual in that it has a very thick coenenchyme in which the polyps are embedded.

Closed appearance of the uncommon zoanthid Neozoanthus growing on the base of a Sarcophyton sp. leather coral. Note sand grains attached to columns.

Protopalythoa vestitus has a distinctive pattern of stripes. Protopalythoa grandis has a rare form with similar stripes.

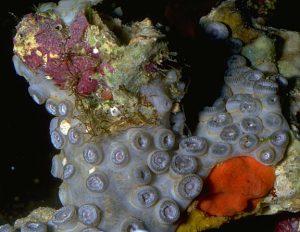

This Palythoa sp. has fluorescent orange pigment, unusual for the genus.

Parazoanthus axinellae from the Mediterranean. A beautiful temperate species that grows freely on rocks, unlike most other members of the genus that associate with sponges and other animals that provide a position for them out in strong currents where they can catch plankton.

Reproduction

Ryland, and Babcock (1991) describe the reproductive cycle of Protopalythoa on the Great Barrier Reef in Australia. There it spawns along with corals during the mass spawning event during the week after the full moon in November. Zoanthids may have separate sexes, but some are also hermaphrodites (Fosså and Nilsen, 1998). The product of the union of gametes develops into a free- swimming larva called Zoanthina for Zoanthus spp., and Zoanthella for Protopalythoa spp (Delbeek and Sprung, 1997).

Competitive interactions

Zoanthids compete for space as do most other sessile encrusting or colonial invertebrates, and they do so by means of toxins or the ability to rapidly overgrow their neighbors. Palythoa and Protopalythoa are toxic and will damage most stony corals and some soft corals. Zoanthus species are more benign, but often overgrow their neighbors. Zoanthus spp. are easily stung by the sweeper tentacles of many scleractinian corals, and also by sea anemones. Zoanthus spp. generally are safe to place adjacent to most soft corals, however. Yellow polyps should not be placed where they will contact soft corals of the genus Clavularia. Yellow polyps, Zoanthus, Protopalythoa and Palythoa spp. can all be grown adjacent to each other with no harm done to any of them.

Zoanthus

Members of this genus are the most colorful of the zoanthids, being shades of green and brown typically, but sometimes fluorescent red, orange, pink, lavender, blue, yellow, or gray, and usually two-toned. They form colonies of densely crowded polyps attached in a common tissue at the base. Some varieties form branched stolon-like creeping bases that tightly adhere to the substrate surface. One form recently imported for aquaria has polyps imbedded in a thick coenenchyme, much like Palythoa spp. Many species grow in the intertidal zone, being exposed at low tide to the baking sun, cold fronts, or to rain showers. They slowly release the water they retain in their columns in order to prevent either desiccation or damage from freshwater during a heavy rainstorm.

Zoanthus spp. do not need to be fed directly, since they obtain much of their nutritional requirements from their symbiotic zooxanthellae. They must therefore be provided with adequate illumination to thrive. They also ingest dissolved organic substances from the water, as well as fine particulate matter. Some species do not take large particles of food, while others do take and eat such things as flake food, blackworms, shrimp, and sea urchin eggs. Regular feeding promotes rapid growth.

In the Caribbean there are two species commonly known and described_, Zoanthus sociatus_ and Z. pulchellus. In south Florida there are two additional species apparently never formally described. One of these undescribed species ( Zoanthus n.sp. 1 in my photos) lives only intertidally, on rocky jetties at inlets where the ocean feeds into the intercoastal waterway. It forms continuous thick sheets of coenenchyme with the polyps imbedded, and the colors of the polyps sometimes include fantastic combinations in bright hues. This species is commonly mixed with Z. sociatus and Z. pulchellus where it occurs, and it is easily distinguished from them. The other undescribed species ( Zoanthus n.sp. 2 in my photos) forms very small colonies of just a few to perhaps a few dozen polyps, usually on hardbottom reefs in sandy areas. The polyps are spaced widely and connected by a stolon. They are typically bright green, but may also be dark blue-gray

or sometimes brilliant turquoise blue. The polyps are small and flattened, considerably smaller in diameter and height compared to Z. sociatus. Zoanthus sociatus forms large colonies of polyps connected at their bases by a very thin coenenchyme, so loosely connected are they that individual polyps or clumps of polyps readily break off of a colony if tugged. The coloration is variable but is generally shades of green or blue-green, often with a yellowish oral cone. Zoanthus pulchellus is found mainly on offshore coral reefs, though it can occur in inlets. It has larger polyps than Z. sociatus, and perhaps larger than any other species of Zoanthus. Zoanthus pulchellus readily accepts food while Z. sociatus does not._ Zoanthus pulchellus_ is also more variable in coloration, being shades of green, gray, pink, or fluorescent red. Colonies of this species may cover large areas of reef substrate, particularly on back reef rubble.

A single polyp of Protopalythoa. Note the tapering tentacles. The tentacles in Zoanthus are by comparison usually shorter and blunt tipped.

A fluorescent red Zoanthus sp. on a reef slope in the Solomon Islands.

This undescribed Zoanthus sp. from South Florida forms sheets covering rocks in places with strong currents, such as inlets. This one is a nice combination of pink, blue, and green.

This undescribed Zoanthus sp. from South Florida grows in small colonies with the polyps connected by a stolon-like coenenchyme.

Several species of Zoanthus are commonly imported for the aquarium trade mainly from Indonesia and Singapore. Based on their similarity to two of the Caribbean species it seems to me that some of them may have circumtropical distributions, though I have not seen anything in the literature to suggest that is the case.

Protopalythoa

Members of this genus were previously referred to as Palythoa spp. in scientific and aquarium literature. Muirhead and Ryland (1985) separates this genus from Palythoa, which has its polyps deeply embedded in the coenenchyme. The fact that there are species with intermediate structure, such as Palythoa mammillosa, suggests that this distinction is of questionable significance. Borneman (1997) also discusses this issue. Nevertheless the majority of species of Palythoa can readily be distinguished from Protopalythoa based on this characteristic. Protopalythoa spp. have the largest polyps of all the zoanthids. They have slimy thick tissue, often with some sand grains trapped on the lower portions of the columns of each polyp. Protopalythoa spp. may occur on reef slopes, but are most common on sandy reef flats and hardbottoms in shallow or deep water. Most species are brownish, sometimes with green oral discs. Some varieties have striped or mottled oral discs. These zoanthids always remind me of the insect-eating plant known as “Venus flytrap,” since they have tapering tentacles around the margins of the oral disc quite like the pointed “eyelashes” that fringe the food capturing structures of the aforementioned plant. The plant and zoanthid polyps also slowly close around their prey in a similar fashion. Protopalythoa spp. have symbiotic zooxanthellae and must be kept under moderate to strong illumination to thrive.

Protopalythoa spp. have toxic mucus that is able to destroy scleractinian coral tissue, so be careful not to place colonies where they are likely to contact stony corals. I’ll discuss this toxic mucus in more detail later in the article.

Protopalythoa spp. all take food when it is offered. They feed on meaty things such as shrimp, worm, or mollusk flesh, and will also take fish eggs, invertebrate eggs, flake foods, and pellet foods.

Three easily identified species are worth distinguishing from the rest, Protopalythoa grandis, P. psammophila, and P. vestitus. My favorite is Protopalythoa grandis, which has polyps up to two inches in diameter, and mottled in shades of brown, white, and green. It apparently has circumtropical distribution (Colin and Arneson, 1995), but colonies harvested for the aquarium trade come mainly from deep hardbottom reefs in the Gulf of Mexico off the Florida coast. To grow this species it is necessary to offer food regularly. Without adequate food supply the polyps shrink slightly and the fringe of tentacles degenerates to the point that the polyps could be confused with Discosoma spp. Protopalythoa grandis has a habit of closing up for several days, during which time it secretes a waxy film that is subsequently shed. This is a normal process that is also seen in Palythoa spp., other (but not all!) Protopalythoa spp., as well as in leather corals such as Sarcophyton and Lobophytum, gorgonians such as Pterogorgia, and the stony coral Porites. Shedding this waxy film is a means of preventing the growth of algae or other organisms on the surfaces of the polyps. Protopalythoa grandis should be placed near the bottom of the aquarium where the illumination is not very intense.

Protopalythoa psammophila ranges across the Pacific and has the desirable feature of being bright fluorescent green. At one time this species was harvested from Hawaii for the aquarium trade, but such harvest ended in the early 1990’s due to new regulations for the state. Many aquarists still grow and propagate the Hawaiian form, but bright green Protopalythoa cf. psammophila are also now occasionally being imported from Singapore and the Sea of Cortez. This species prefers bright illumination, but the most intense color develops under moderate illumination.

Protopalythoa vestitus is a beauty that is widespread in the Indopacific. It has a distinctive pattern of brown and white bands on the oral disc, and may fluoresce green under blue light. It is commonly imported from Indonesia.

Palythoa

Members of this genus all look more or less the same, quite like faviid corals with which they are often confused. As mentioned previously, the coenenchyme is thickened into a cushion in which the polyps are embedded. The coenenchyme also contains sand grains. The color is usually pale yellow or brown, but fluorescent green colonies occur in some regions, and I observed some with fluorescent orange pigment in the Solomon Islands. A small colorful crab, Platypodiella, is associated with this zoanthid and apparently feeds on it, potentially obtaining a benefit from the toxin(s) the zoanthid produces (Delbeek and Sprung, 1997).

Palythoa spp are most common on reef flats or the tops of reefs, where they may form colonies several metres across. They often occur in a zone mixed with fire corals ( Millepora spp.). They may also occur on reef slopes, usually as small colonies. Degraded reefs may become overgrown by them, and they are able to out-compete stony corals.

In the aquarium one should be careful not to place Palythoa where it will contact stony corals. Palythoa spp. grow best under strong illumination, and should be offered planktonic foods, such as copepods, Artemia, or Daphnia.

Isaurus

Members of this genus are commonly called “Snake Polyps.” Three valid species are known, I. tuberculatus, I. cliftoni, and I. maculatus. Isaurus tuberculatus is distributed circumtropically and is the species most commonly seen in the wild and in aquariums. Isaurus spp. have elongate columns with tubercles (bumps) and the columns are typically oriented so that the ends face downward. The tentacles are normally retracted during the day and expand at night to feed on zooplankton. The columns contain zooxanthellae and should be exposed to bright light. Isaurus does not need to be fed to be maintained in captivity, but regular feeding will cause the polyps to multiply. The best foods for Isaurus are Daphnia, Cyclops (copepods), and brine shrimp nauplii.

Yellow Polyps

Although various aquarium references have called this zoanthid a Parazoanthus sp., it is not. That description makes sense when one considers that Parazoanthus spp. are often yellow. For example, several years ago when I discussed “the yellow photosynthetic zoanthid from Indonesia” with world zoanthid expert J. S. Ryland, he assured me that it was probably a Parazoanthus, but he cautioned that his comment was based on the color I described only, not on a specimen. This zoanthid does not yet have a name, nor even a genus. It appears to be related to Acrozoanthus and the undescribed zoanthid I am calling Zoanthus nsp.? in this article.

Despite its lack of taxonomic placement, this zoanthid has had a place in aquariums since the very beginning of the reefkeeping hobby. It is a very hardy beautiful addition to any aquarium. The only downside is that it spreads quickly enough to damage and overgrow corals. Take care to place this species on isolated rocks in the sand or on the glass to avoid having it grow on the reef and approach corals. Care of yellow polyps is simple: give them strong light and feed them. If they are placed in strong water motion they will catch the food offered to the fishes, and do not need supplemental feeding. They eat flakefood, shrimps, worms, or anything meaty and small enough for them to grab.

Acrozoanthus

One species in this genus is frequently imported under the common name “Stick Polyps.” The name arises from the parchment like “stick” on which these polyps occur naturally. The stick is not secreted by the polyps themselves, but is instead the top of a tube formed by a large type of polychaete worm ( Eunice tubifex ) that lives buried in sand. The collectors simply cut off the top of the tube, leaving the worm intact in its home buried in the sand. It can readily build a new extension of its tube upon which more Acrozoanthus can settle.

Acrozoanthus polyps are similar to those of “Yellow Polyps,” but they are larger, brown, and have very long stringy tentacles. Though naturally associated with the worm, these polyps readily adapt to captivity and spread onto rocks. They need to be fed to really proliferate in captivity. They will eat copepods and any chopped meaty foods. Despite their need for food, they do also harbor zooxanthellae, so they should be maintained in a well illuminated aquarium.

Neozoanthus

This uncommonly seen genus forms small colonies of cryptic polyps that are similar in appearance to those of Epizoanthus. They characteristically have sand grains trapped in their tissue. They should be fed with copepods or brine shrimp nauplii, and provided with moderate to strong illumination. I first observed this species as a few polyps on the base of a Sarcophyton sp. from Indonesia.

Parazoanthus and Epizoanthus

Members of these genera are epizootic, meaning they live on other animals. Parazoanthus and Epizoanthus are almost exclusively found associated with sponges and hydroids, though they may also grow on gorgonian skeletons and even freely. They do not harbor zooxanthellae and thus must be fed zooplankton regularly in order to thrive. They occur where there are strong currents that carry plankton, so the water motion in the aquarium housing them should be swift and laminar. The association with sponges is believed to protect the sponges from predators. These zoanthid polyps are toxic and may also sting sponge eaters such as large angelfish.

Predators

Some fishes will eat zoanthids, though most find them distasteful. The box snails, Heliacus spp., feed specifically on zoanthids, and can be considered a pest if one is trying to grow them, or a savior if one is trying to rid the aquarium of zoanthids. It is not always easily seen, as the shell is round and about the size of a closed zoanthid polyp.

A word of caution about Zoanthids

I must mention the fact that zoanthids are quite toxic. They produce a substance known as palytoxin (Mebs, 1989) that is one of the most toxic naturally occurring poisons known. This substance was first discovered associated with Palythoa spp. in Hawaii, but has since been found in Zoanthus as well (Fosså and Nilsen, 1998). Palytoxin is apparently produced by bacteria that live in association with zoanthids. A fascinating account about the discovery of palytoxin can be found online on the Wet Web Media site, see reference given.

A strange side note to this is the anecdotal observation I reported in my column Reef Notes in FAMA magazine that this toxin or another one associated with zoanthids may be able to be aerosolized. An aquarist trying to rid his live rocks of a species of Protopalythoa decided to remove the rocks and spray boiling water on them to kill them. A friend of his contacted me after the aquarist was in the hospital and in serious condition, the doctors unable to determine what had caused a serious reaction and respiratory distress. I pointed out the possibility of a palytoxin reaction, but was skeptical about the aerosol or “toxic fumes” that the aquarist believed made him become ill suddenly. The aquarist later recovered, but slowly. In any case, one should be extremely careful when handling zoanthids, Protopalythoa and Palythoa spp., in particular. Rinse your hands thoroughly with soap and water immediately after contacting them.

References And Suggested Reading

- Borneman, (1997) E. Zoanthids Coral? Anemone? Both? Neither? Aquarium Net. http://www.aquarium.net/0198/0198_1.shtml

- Burnett, W.J., et. al. 1997. Zoanthids (Anthozoa, Hexacorallia) from the Great Barrier Reef and Torres Strait, Australia: systematics, evolution and a key to the species_. Coral Reefs_ 16: 55-68.

- Coll, J.C., and P.W. Sammarco. 1988. The role of secondary metabolites in the chemical ecology of marine invertebrates: a meeting ground for biologists and chemists_. Proc. 6th Int’l Coral Reef Symp_, Australia, 1: 167-73.

- Delbeek, J.C. and Julian Sprung. 1997. The Reef Aquarium. Volume 2. Ricordea Publishing,., 546 pp.

- Fosså, S. and A. J. Nilsen (1998). The Modern Coral Reef Aquarium Volume 2. Birgit Schmettkamp Verlag

- Koehl, M.A.R. 1977. Water flow and the morphology of zoanthid colonies. Proc. 3rd Int’l Coral Reef Symp. 437-44.

- Mather, P. and I. Bennet (eds.) (1993). A Coral Reef Handbook 3rd Ed. Surrey Beatty and Sons PT Ltd., Chipping Norton, NSW Australia.

- Mebs, D. (1989). Gifte im Riff. Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft mbH, Stuttgart, Germany.

- Muirhead and Ryland (1985). A review of the genus Isaurus Gray, 1828 (Zoanthidea), including new records from Fiji. Jour. Nat. Hist. (19): 323-335.

- Ryland, J.S. and R.C. Babcock (1991). Annual cycle of gametogenesis and spawning in a tropical zoanthid, Protopalythoa sp. Hydrobiologia (216/217): 117-123.

- Sebens, Kenneth P. 1977. Autotrophic and heterotrophic nutrition of coral reef zoanthids. Proc. 3rd Int’l Coral Reef Symp. 397-404.

- Sprung, J. (2000) Invertebrates: A Quick Reference Guide. Ricordea Publishing. Coconut Grove, Fl. USA.

- FAQ’s about zoanthids and other polyps 1. http://www.wetwebmedia.com/zoanthid1.htm

0 Comments