I received this very flattering email several weeks ago:

Terry,

First, I would like to congratulate you on all your work. I’ve read all your articles from Aquarium Frontiers and I just love them all. Also, I think your tank is simply one of the most natural I’ve ever seen. After that, I would like to know if you still have that 12-gallon tank with Dendros & Alveoporas that appeared in an article in Aquarium Frontiers. If so, how’s the setup? Do you have any photos of it?

Eduardo Cavalcanti, Brazil

It reminded me of mine and J. Charles Delbeek’s attempts at keeping Dendronephthya spp._ _alive in captivity. Neither of us considered ourselves successful at maintaining this and other nonphotosynthetic corals. See, http://www.advancedaquarist.com/2002/1/aafeature.

Though Delbeek’s setup was more elaborate than mine, we both attempted to feed Dendronephthya spp. the correct sized phytoplankton, presented at the correct water motion. The correct prey delivered at the appropriate water velocity was based on the research of others in the field. It is true that both of us were able to keep our small colonies of Dendronephthya alive considerably longer than if we didn’t try to feed them, we were nonetheless unable to keep these colonies longer than 6 to 9 months, during which time they clearly grew smaller, indicating starvation. For those unfamiliar with nonphotosynthetic corals, it is important to recognize that these corals get their entire food budget from feeding – they do not get any food from symbiotic algae (zooxanthellae), as do photosynthetic corals.

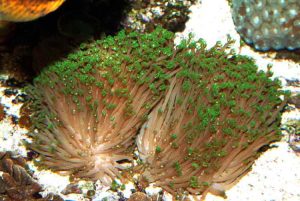

This Alveopora specimen has been with the author for two years, during which time it has doubled in size.

A possible reason for our lack of success came via implication in Dr. Yehuda Benayahu’s talk, entitled Early Developmental Stages of Soft Corals: Crucial Adaptations for Survival, delivered at the just past MACNA in Dallas/Ft.Worth.

Dr. Benayahu, with help from his graduate students studied, along with other corals, Dendronephthya hemprichii. One of the things that became clear when studying the reproductive behavior of this coral is that Dendronephthya hemprichii is that, unlike most corals, is continuously engaged in reproduction. Also, when the conditions are favorable, given its reproductive strategy and growth rate, it can rapidly populate an area.

I would therefore speculate that when kept in captivity it attempts the same strategy, but given the limited availability of food this same strategy becomes counter productive. To be continuously seeking to reproduce requires a large food budget, and within a captive system such conditions cannot be easily met. Interestingly, Dr. Yehuda Benayahu pointed out that he and his students were unable to keep this coral healthy and reproducing even in open water systems. Again, I speculate that the problem was insufficient nutrition for this very demanding coral.

Mr. Cavalcanti also asked about my success or failure with Alveopora spp. I’m happy to report that with one individual specimen I’m having great success. My Alveopora sp. has been sitting on the substrate of my display tank for more than two years, during which time it has doubled in size. It receives moderate light and water motion. During the day time this photosynthetic coral extends its polyps to a length of about three inches, and entirely withdraws them at night.

I don’t think reef keepers ought to believe that this genus is therefore easy to maintain. Like Goniopora spp., most aquarists find that they rarely live beyond 6 to 9 months in captivity. However, based on a number of anecdotal observations where individuals of this genus have been kept long term there appears to be one common condition, which is that in all of these cases that I have knowledge of these corals where placed on their respective reef tank’s substrate. Given the few success stories compared to failures with these genera one can hardly take this as definitive, but it is a possible clue toward the successful maintenance of these corals. What lends a little more credibility to this hypothesis is that most of these genera in the wild are found on the muddy or sandy bottom of lagoons.

One of the things that make our struggle to keep the difficult and hard to feed alive worth our efforts is the kind of experience transmitted by Lisa Page in Photo Gallery in this month’s issue. Her struggle and success with her basket star ( Schizostella bifurcata ) is quite noteworthy.

0 Comments