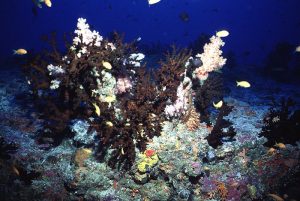

You plunge into the crystal clear water and begin to descent down to the top of the reef. Curtains of plankton feeding fishes rise and fall in the water column as predators approach and then swim past. The light is bright here and provides partial sustenance for the many stony coral colonies that cover much of the bottom. As you move down the reef face, you notice that soft corals become more common. Huge leather corals, patches of Xenia and Sinularia are interspersed between their calcareous relatives. Gradually the soft corals become the most dominant form of live bottom cover. Gorgonians also become a conspicuous feature of the underwater aquascape. Long whip corals protrude from the bottom and the occasional huge sea fan grows perpendicular to the prevailing currents. You encounter the occasional colony of green cup coral (Tubastraea micrantha), that looks like an old gnarled tree growing from the sea floor. Another animal that is more abundant as you move deeper are the sponges. These include smaller encrusting varieties as well as large pastel colored tubular forms.

At a depth of about 140 feet the reef slope flattens out to form a terrace. The terrace is covered with coral rubble with small patches of the calcareous green algae, Halimeda, and the occasional soft coral colony. The terrace gradually becomes a slope and you continue to descend. At a depth of about 200 feet the bottom consists mainly of sand with the occasional patch of hard substrate. This provides an attachment site for the relatively few species of hard and soft corals that live at these depths. Most of these corals do not contain the symbiotic dinoflagellate, zooxanthellae. Instead, they are heterotrophic, feeding on plankton, dissolved organic matter, and detritus. Not only does the aquascape change as you progress down the reef, so to does the fish community. We encounter fishes in these deep water habitats that we rarely, or never see, in shallow parts of the reef.

Deep reefs have long been of interest to adventurers and aquarists alike. Although they are typically not as “lush” (i.e., species rich) as the more brightly-lit reef face, deep reef slopes and terraces provide a home to an interesting and unique assemblage of invertebrates and fishes. With the increase of collecting in deepwater environments, it is now possible for the aquarist to recreate deep reef fish communities in their home aquarium. The purpose of this article to examine some deep reef fish communities, and to discuss the special care requirements of fishes from these habitats. Hopefully by doing so the potential deepwater reef aquarist will be able to successfully model this unique biotope. A logical starting point is to define what we mean by a deep reef fish community.

What is a “Deep Reef Fish Community.”

What do we mean by a deep reef fish community? Although “deep” is an arbitrary term, in this article we will refer to those fishes that live on or adjacent to corals reefs, at depths in excess of 100 feet as deep reef fishes. Many fishes we find on deep reefs also occur at more shallow depths. For example, the firefish (Nemateleotris magnifica) can be found at a depth range of 20 to 200 feet, but this species is frequently encountered in the shallower part of this range. In this article we will limit our coverage to those fish species that are most numerous at depths in excess of 100 feet, as well as those species that are restricted to greater depths. There are a number of reef fish that fall into the first category. For example, the longnose hawkfish (Oxycirrhites typus) is most frequently encountered on black coral trees or on gorgonians at depths in excess of 100 feet. However, in some areas it has been observed at depths as shallow as 35 feet. Other species that are occasionally found on shallow reefs, but are most often found at greater depths include Randall’s anthias (Pseudanthias randalli), the red-belted anthias (Pseudanthias rubrizonatus), the harlequin hind (Cephalopholis polleni), the blackcap basslet (Gramma melacara), the olive chromis (Chromis insolata), Colin’s angelfish (Centropyge colini), the multicolor angelfish (Centropyge multicolor), Nahacky’s angelfish (Centropyge nahackyi), and the bluethroat triggerfish (Xanthichthys auromarginatus). Fish species that are for the most part restricted to deep reef habitats are less common in the aquarium trade. For example, the rhomboid fairy wrasse (Cirrhilabrus rhomboidalis) has only been reported at depths in excess of 124 feet, the Spanish flag (Gonioplectrus hispanus) occurs at a depth range 200 to 1200 feet, the cave bass (Liopropoma mowbrayi) is found at depths in excess of 100 feet, while the longfin anthias (Pseudanthias ventralis), which has been reported in water as shallow as 91 feet, is not common until one exceeds a depth of 130 feet.

There are a number of factors that interact to determine the bathymetric distribution of a reef fish species. Biotic characteristics of a fish’s environment, like the presence of particular food items, competitors, and predators, can affect a fishes depth range. Also abiotic variables, like the substrate type, the presence of shelter sites, light levels, water movement, water temperature, and other specific microhabitat “preferences” are contributing factors. There is a phenomenon referred to as tropical submergence, where an organism occurs at greater depths the closer you get to the equator. For example, the masked angelfish (Genicanthus personatus) is common at depths between 50 and 85 feet around the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, while it is rarely seen off the more southern islands in the chain, and when encountered it usually occurs at water depths greater than 130 feet. As you get closer to the equator the ocean’s surface temperatures typically get warmer. This factor apparently causes some fish species to retreat to cooler, deeper waters. In the case of the masked angelfish, the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands are also bathed by colder currents then the southeastern islands.

The depth range occupied by some reef fish species is a function of the geological characteristics of the reef that they are living on. For example, some outer reefs, especially those on the leeward side of islands, can consist of a steep wall or drop-off. On reefs of this sort, fishes that are often more abundant in deep reef habitats will stray into shallower habitats. Some fishes are also encountered at different depths at different stages of their development. For example, the chevron or black bristletooth (Ctenochaetus hawaiiensis) is found at wider range of depths as an adult (including very shallow water) then it is as a juvenile (Hoover [1993] states that the juveniles are most common at depths of 60 to 100 feet in areas with heavy stony coral growth]).

Deep-reef Fishes

I would like to survey some fish families that are both of interest to aquarists and that contain representatives that occur in deep reef environments. Note that not all the fishes discussed below are suitable for the reef aquarium. I will point out those species that may harm ornamental invertebrates.

Anthias

Nothing in the underwater world makes my heart flutter more than a beautiful shoal of anthias! These fishes are often sought after by reef aquarists because they present no threat to ornamental invertebrates. The subfamily Anthiinae contains a number of species that are restricted to depths greater than 100 feet and many more are most common in deep water. Many of the anthias have special care requirements and are not suitable for all aquariums or aquarists (see Michael 1998 for more details). One of the most effective way to keep these beautiful fishes is to attach a refugium to your aquarium with a healthy community of small crustaceans, like copepods and amphipods. The best refugia are those that flow directly into the display tank and/or are mounted inside the aquarium. (There are several companies that make wonderful acrylic refugia that hang on the side of the tank or hang on or sit-on the aquarium sump, including Creative Plastic Resources [CPR], EcoSystem Aquarium® and Inland Aquatics.) With a refugium you can provide these active planktivores with a continual source of nutritional fare.

If you do not use a refugium, you should feed your anthias at least three times a day (some individuals will survive on two meals a day). Some of the healthiest anthias I have ever seen were fed live brine shrimp that were being “dripped” into the tank for most of the daylight hours. I have yet to use one, but Oscar Enterprises Inc. makes a brine shrimp hatchery (known as the Continuous Hatch’n and Feeder) that attaches to the side of the tank. As the eggs hatch, the baby shrimp are attracted to the lights and gradually move out of the hatcher and into the aquarium where the fish can eat them. This may be another effective way to help your anthias (and other active zooplanktivores) to get enough to eat. You should also offer a nutritionally rich form of food as a staple, like frozen mysid shrimp (this is a great first food to get finicky individuals to eat), vitamin enriched brine shrimp, a frozen preparation for carnivores and a color enhancing flake food.

Some of the anthias that are usually restricted to depths in excess of 100 feet include twinspot anthias (Pseudanthias bimaculatus), onestripe anthias (P. fasciatus), Hawaiian longfin anthias (P. hawaiiensis), diadem anthias (P. parvirostris) and the longfin anthias (P. ventralis). All these species do best if housed in a more dimly-illuminated aquarium. If you can acquire healthy individuals, the twinspot and onestripe anthias are moderately hardy, although they get larger and need plenty of living space. The twospot anthias can also be quite aggressive toward conspecifics and other anthias. Of all these species, the diadem anthias (P. parvirostris) is a great choice! Individuals are most often collected in the Maldives. It is a smaller species that readily adapts to captive life. Both the longfin and Hawaiian longfin anthias are sensitive and only suitable for the more experienced hobbyist. I have also seen a number of Hutomo’s anthias (Pseudanthias hutomoi) in holding tanks at Los Angeles fish wholesaler. (This species is usually found at depths in excess of 130 feet.). A single individual I kept proved to be a voracious feeder, but eventually perished (it became more and more emaciated, no matter how much I fed it, and finally died). I have heard from Japanese hobbyists that this fish is not difficult to keep, so my specimen may have been an exception for the species, not the rule.

Male and female Hawaiian longfin anthias (Pseudanthias hawaiiensis) – from deep reefs off the Hawaiian Islands.

There are also anthias species that are sometimes encountered at shallower depths, but are most abundant in deeper water. These include Lori’s anthias (P. lori), the squareblock anthias (P. pleurotaenia), Randall’s anthias (P. randalli), redbelted anthias (P. rubrizonatus) and the princess anthias (P. smithvanizi). Most of these anthias occur on reef drop-offs and can be housed in a reef aquarium with a steep reef profile. Of these species, the redbelted is the most hardy, but it can also become quite pugnacious towards conspecifics and other anthias. The squareblock is beautiful and common in the trade. Healthy individuals, adapt readily to captive life and can be sturdy aquarium inhabitants. They are a larger species that needs plenty of room to move! Like many of the other anthias species, keeping groups can be difficult because of intraspecific aggression.

There are also two species in the genus Holanthias that are showing up in aquarium stores. These fishes tend to be hardier then most of their Pseudanthias relatives and are most abundant at depths in excess of 200 feet. The Hawaiian Deep-water anthias (Holanthias fuscipinnis) is a Hawaiian endemic that is sporadically available. It is an expensive fish that thrives in captivity. When initially introduced to the aquarium this fish may hide for several days or even lay on the bottom. But if they are placed in a well maintained aquarium that does not contain overly aggressive tankmates, they will snap out of it. The roughtongue bass (Holanthias martinicensis) is a hardy resident of the tropical western Atlantic. This species does better at lower water temperatures. It tends to be a very durable aquarium fish that is not overly aggressive and can be kept with other deepwater anthias and smaller zooplanktivores. It is prudent to house only on male per tank, unless the aquarium is of considerable size. The majority of individuals collected are sent to Japan and command a very high price.

The deepwater genus Hemanthias is also represented in the aquarium trade. The streamer bass (Hemanthias vivanus) is collected on deep reefs in the western Atlantic and is a durable aquarium fish. It should be kept at cooler water temperatures (below 76 º F) in a dimly-lit tank.

Groupers

Not only are there many anthias present in deep reef habitats, there are also groupers belonging to other serranid subfamilies. In the tropical western Atlantic there are a number of deepwater members of the subfamily Serraninae, the dwarf basses. These include the orangeback bass (Serranus annularis), the chalk bass (S. tortugarum), and the tattler bass (S. phoebe). Unlike the anthias these fishes are very durable and are suitable for aquarists with a wide range of experience. They can be housed in the reef aquarium, but some may eat your ornamental shrimp. The chalk bass is an especially welcome addition to the reef tank. This fish is not aggressive (it can even be kept in small groups in the aquarium) and is less likely to bother motile invertebrates. It is typically found over rubble or sand bottoms at depths of 40 to 1,290 feet. The tobacco fish (Serranus tabacarius) is another member of this group that is often found at depths in excess of 100 feet on sand flats adjacent to the reef slope.

Another deepwater western Atlantic serranid that has only recently been made available to marine aquarists is the Spanish flag (Gonioplectrus hispanus). This fish is in the subfamily Epinephelinae and is typically found at depths in excess of 200 feet. It occurs on bank reefs and usually lurks in caves and under overhangs. The Spanish flag is a very durable aquarium fish, but it is also a voracious predator that will consume small fishes and crustacean tankmates. The harlequin hind (Cephalopholis polleni) is another spectacular deepwater member of this subfamily. This Indo-Pacific species is also a cave-dweller that often swims upside down, with its belly directed toward the cave ceiling. On rare occasions, this hind is observed at depths of less then 80 feet on steep walls, but it is usually found in more than 120 feet of water. It is a very durable fish that is also dangerous to small fishes and crustaceans. Both of these species command a high price.

The members of the subfamily Liopropomini, known commonly as reef basslets, are highly desirable serranids that are well-suited to the smaller reef aquarium. Although they will eat ornamental shrimps and crabs, they are more diminutive and thus less of a threat to these animals than many of their grouper cousins. There are several tropical Atlantic forms that make it into aquarium stores. One of these, the Swissguard bass (Liopropoma rubre) use to be a rare find in aquarium stores, but now it is regularly available. However, it cannot be classified as a deep-water reef fish (that is, it is abundant at depths of less than 100 feet).

The two other species of Atlantic reef basslets are less common, and very expensive. Two species, the candy bass (Liopropoma carmabi) and the cave bass (L. mowbrayi), are being collected at great depths (in excess of 200 feet). The candy bass is one of the most exquisite of all reef fishes. It is quite secretive, spending much of its time moving among the aquarium décor, but it has a peaceful disposition. It will become bolder with time and is more likely to make its presence known in a dimly lit aquarium. The wrasse bass (Liopropoma eukrines) is found on deep bank reefs in the Gulf of Mexico and along the south east coast of North America. It is typically found at depths in excess of 100 feet, where it occupies caves, crevices, and ship wreckage. This species attains a larger size then its aforementioned congeners, and thus is a greater threat to a wider range of fishes and crustaceans.

Recently, Dennis Reynolds of Aquamarines sent me a very interesting Liopropoma spp. that turns out to be a new species. This particular reef basslet has been observed before by Dr. Richard Pyle on deep reefs (greater than 260 feet) all over the Western and South Pacific. Although it is not always easy to get good, specific collection data for individuals collected for the aquarium trade, the two specimens I received from Dennis were reportedly captured in the Flores Sea, Indonesia. We believe that they were also collected at depths much less than those were Richard had spotted it in the past as most fish collectors in this area would not dive to depths of 260 feet. Dr. Pyle and fellow fish expert John Earle will be describing this species, and several others in the near future. As far as its aquarium care is concerned, it seems to be like others in the genus. Somewhat shy and needing good shelter sites in order to thrive.

Orangeback bass (Serranus annularis) – a small serranid typically found at depths in excess of 100 feet.

In the next issue we will finish our examination of reef fishes from deep reef communities. Until then, happy fish-watching!

0 Comments